(source: finnholbek.dk)

Miss Julie Bjelke (1774-1845) born Christine Julianne Fredrikke Charlotte von Bjelke, but apparently only used Julie von Bjelke. Daughter of Amtmann (governor) Bjelke i Tønder Amt i Slesvig. She spent much time in Slesvig and Copenhagen, but as part owner of the copper mines in Røros, she also spent time in Trondheim (Norway), and likely also in Christiania.

Being a fearless woman unwilling to adhere to customary behaviour for women of nobility. This of course led to some amount of critique and ridicule, and Trondheim merchant Christian Thaulow referred to her as a difficult woman. He claims in his book Personalhistorie for Trondhjems by og omegn (1919) that the board of the Røros copper mines had much trouble with this woman and that she was quarrelsome and difficult to do business with. I expect the men in power were not happy to encounter a woman they could not push around.

A less dismissive account of Miss Bjelke could be found in Ragna Nielsen’s book of 1904 Norske Kvinder i det 19de Aarhundrede (Norwegian women in the 19th century).

Ragna Nielsen (1845-1924) was a teacher, leader of the women’s votes organisation, established the renowned school Ragna Nielsens Skole and also Kristiania Hvindelige Handelsstands Forening (Organisation of Christiania Women in Buiness) and more.

https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ragna_Nielsen

Nielsen points out how the annoyed and aghast people of convention would aim, and often succeed, to attach a sense of ridicule to women who did not conform. She notes that even half a century later the mention of Julie von Bjelke would produce a little smile and shrug.

Anne Lister did certainly not approve of her,

“Mademoiselle Bielca sent to say she would call – here from 1 ½ to 2 ¼ past middle age 2nd rate person – prosing – could not understand her inquiring after Mrs Courtenay Stuart”.

You would think Anne Lister would perhaps like her, but Anne apparently did not prefer women who resembled herself. She writes about her lack of admiration for learned ladies in entries about her friend Miss Pickford (Febr 1823):

“they think her blue and masculine. She is called Frank Pickford (...) [she] is certainly like a gentlewoman and clever (...) [she] supposes me like herself. How she is mistaken! (...) she is better informed than some ladies and a godsend of a companion in my present scarcity, but I am not an admirer of learned ladies. They are not the sweet, interesting creatures I should love” – Helena Whitbread, The secret Diaries of miss Anne Lister (pp 255-259)

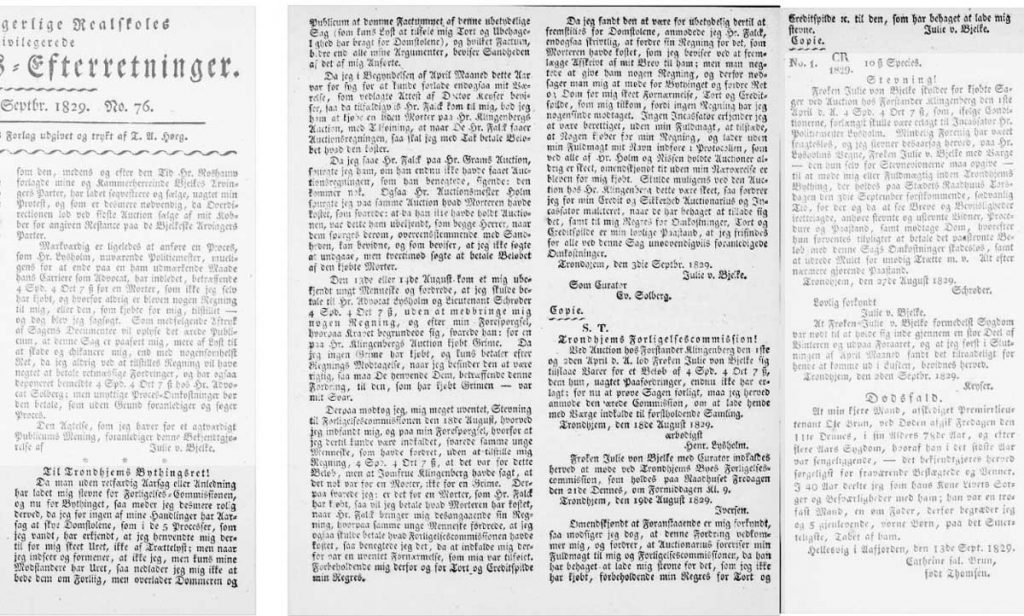

Miss Bjelke deserved more credit, she was a fighter in a male dominated world much like Anne Lister herself. One example from Nielsen book tells of a situation where the local (Røros) customs authorities demanded that Miss Bjelke pay additional taxes of 1109 Speciedaler and 7 Skilling more than she found to be correct (equivalent of about £26,800 / NOK 323,000 today), upon her refusal they seized her 30 Skippund (almost 4,8 tons) of Copper and planned to sell it at an auction on 6. August 1823. But Miss Bjelke immediately hit the roads, that were so wet and poor that she must travel two nights in a row to make it up to Røros in time, and managed to arrive 2 hours prior to the auction, made an objection to its legality and salvaged her copper. The local court then ruled against her but the regional court and supreme courts overturned it and ruled in her favour.

Another time Miss Bjelke took the works to court for ‘reckless and unreasonable administration’, it resulted in a long, drawn out legal process that ended in the (copper)works being ordered to pay Miss Bjelke 1772 Spesiedaler and 19 1/2 Skilling, after retrials and the works hiring renowned lawyer Fredrik Stang, the payment to Miss Bjelke finally came to 242 Speciedaler and 4 Skilling. Whenever Miss Bjelke found something was not right, she would object, and this was – and here Nielsen quotes Thaulow – why Miss Bjelke was considered so difficult and had many enemies. But, Nielsen points out, she won all 5 of the cases she brought against the administration of the copper works, so she must have had the law on her side.

She did not, however, simply take care of her own rights and properties, she was very generous towards the ‘needy and the poor’, and was a board member since 1828 of De Nødlidendes Venner (Friends to the suffering). She was a brave woman, and apparently spoke with both wisdom and authority. She wrote pamphlets and articles on justice, oppression, property law and the constitution, and about the Røros copper works’ administration.

bigger image